.Holocaust survivors and their memories are at the core of this exhibition

?What can we learn from these witnesses

Opening: Mach 2019

The fear, the persecution and loss of loved ones have left deep and unhealable wounds in those who were then children and teenagers. These people bear scars that cannot be healed. The last goodbye, the last visual contact with a father, a mother, a sibling has marked their memories permanently. At the same time, the quotes show that the witnesses have tried to cope with their wounds in very different ways over the course of their lives.

The survivors know that they are exceptions. They were lucky, but they also feel that they don’t deserve this luck. The fact that they have survived, while their relatives were killed, is

incomprehensible and remains a heavy burden for many survivors.

The Holocaust a genocide and a break with civilization that stands as an unfathomable dark period in 20th-century history becomes vivid and concrete in the reports given by the witnesses to it. Their stories serve as evidence that the Holocaust is neither indescribable nor inconceivable. It is the outcome of numerous events that developed over many years in various European places. It was not the work of a primitive society, but of a nation with a great cultural history. The witnesses do not speak of barbarians or beasts, but of other people. People who tortured them horribly, who “only did their duty”, who watched or looked away or tried to help.

For a long time, barely anyone listened to survivors. For years, even decades, many of them could not or did not want to speak about their persecution. Listening to them is a key aspect in confronting the Holocaust. However, explaining the Holocaust is the mission of historical research, which looks in the eyes of victims, perpetrators and bystanders equally

THE LAST SWISS HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS

As a neutral country, Switzerland came out of the World War II unharmed. Who are the Holocaust survivors in Switzerland? The vast majority were not Swiss citizens at the time. They came from the German Reich or other European countries; and as Jews, they were a direct target of Nazi persecution. Some survived concentration camps and extermination camps; others saved themselves by escaping or hiding. Most arrived in Switzerland after World War II.

From 1933 to 1938, thousands of Jews, political opponents, Roma, Sinti, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and homosexuals who had been excluded and persecuted managed to get to other countries via Switzerland. After the war broke out, the determined authorities made the “continuation of the journey” almost impossible, and a few hundred people remained in Switzerland and survived. Because Switzerland closed its border to refugees, only an illegal path remained in 1939. After deportations of Jews had begun, and Switzerland remained the last chance for many, several thousand Jews were sent back to the border, even though as of 1942 the authorities knew that they would face death.

However, those who managed to secretly get into the interior of the country were not expelled, but placed in camps. By the end of the war, there were over 50,000 refugees in Switzerland about 20,000 of whom were Jewish even though Switzerland did not recognize the persecution of Jews as grounds for asylum until July 1944. Since the government only became involved with refugees at a late date, private welfare organizations had to support the financial costs. For many years, the Association of Swiss Jewish Refugee Aid and Welfare Organisations took care of thousands of people, and the 19,000 Swiss Jews, as well as the umbrella organization, the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities, carried an enormous financial burden. They received some support from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

After the war ended, Switzerland provided humanitarian assistance and allowed young people liberated from Buchenwald to recover in sanatoriums, for example. However, they soon had to leave the country again. After the Hungarian uprising in 1956 and the Prague Spring in 1968, several thousand refugees were admitted. Among them were some Holocaust survivors, who were not considered Nazi victims, but rather opponents of the Communist regime. The fact that there are Holocaust survivors in Switzerland entered public consciousness at the time of the debate over dormant assets and the historical research of the Bergier Commission in the late 1990s.

In 2017/18, Switzerland holds the Chairmanship of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The exhibition The Last Holocaust Survivors in Switzerland gives a say to the last witnesses of the Holocaust and their descendants.

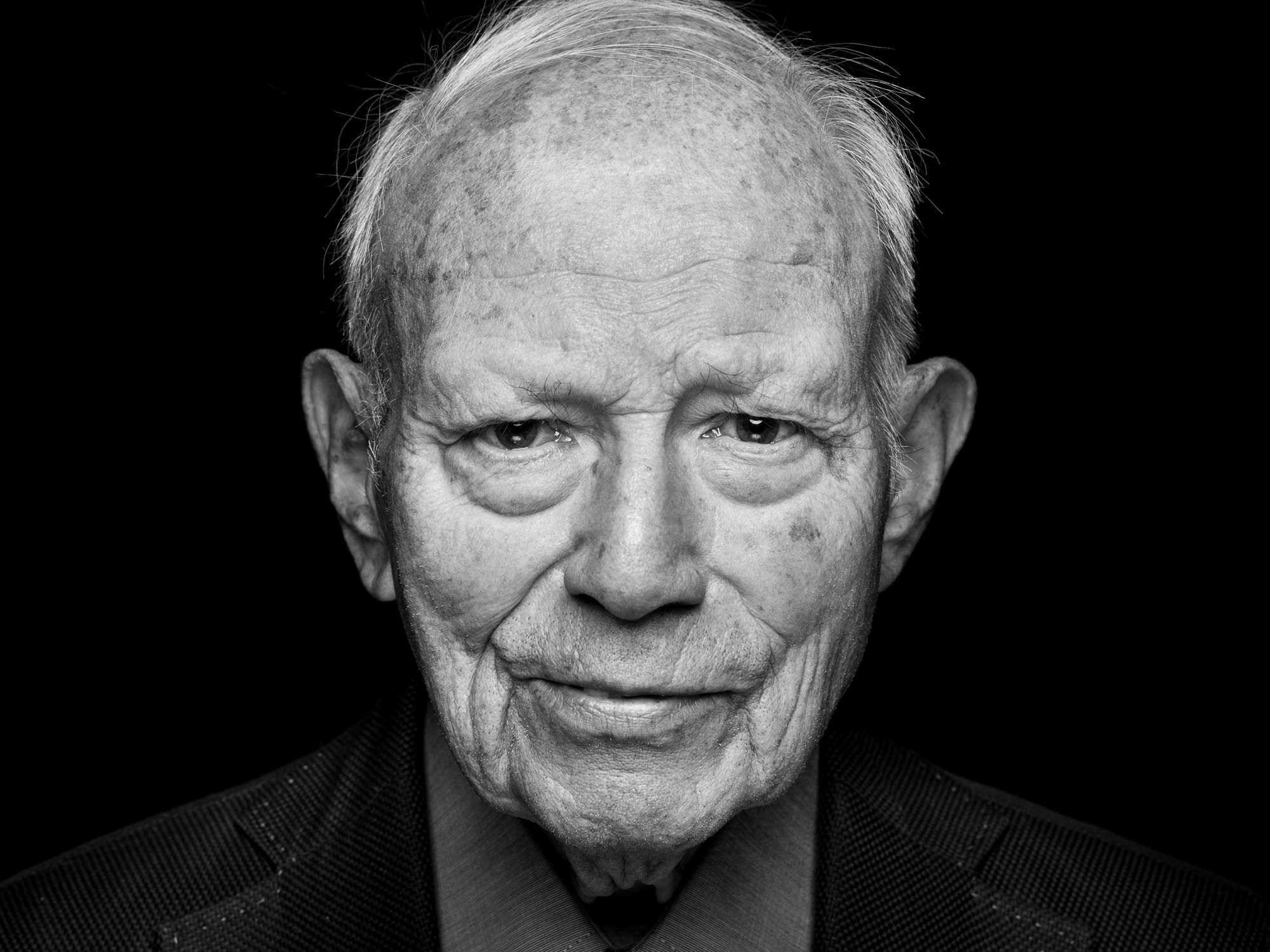

KLAUS APPEL

We were at home when the doorbell rang. “Are you Mr. Appel? Then come with us.” My father turned to me and said: “You go to school.” This is the last thing he told me. I never saw him again.

Klaus Appel was born in Berlin in 1925. After his father’s arrest, Klaus and his sister Ruth got on one of the last Kindertransports to England. His older brother, 20-year-old Willy-Wolf, was arrested and murdered at Auschwitz like their father, who was 45 years old. After the war, Klaus met a Swiss woman. He worked as a watchmaker and lived in the French-speaking part of Switzerland where he passed away in April 2017. He has two children and three grandchildren.

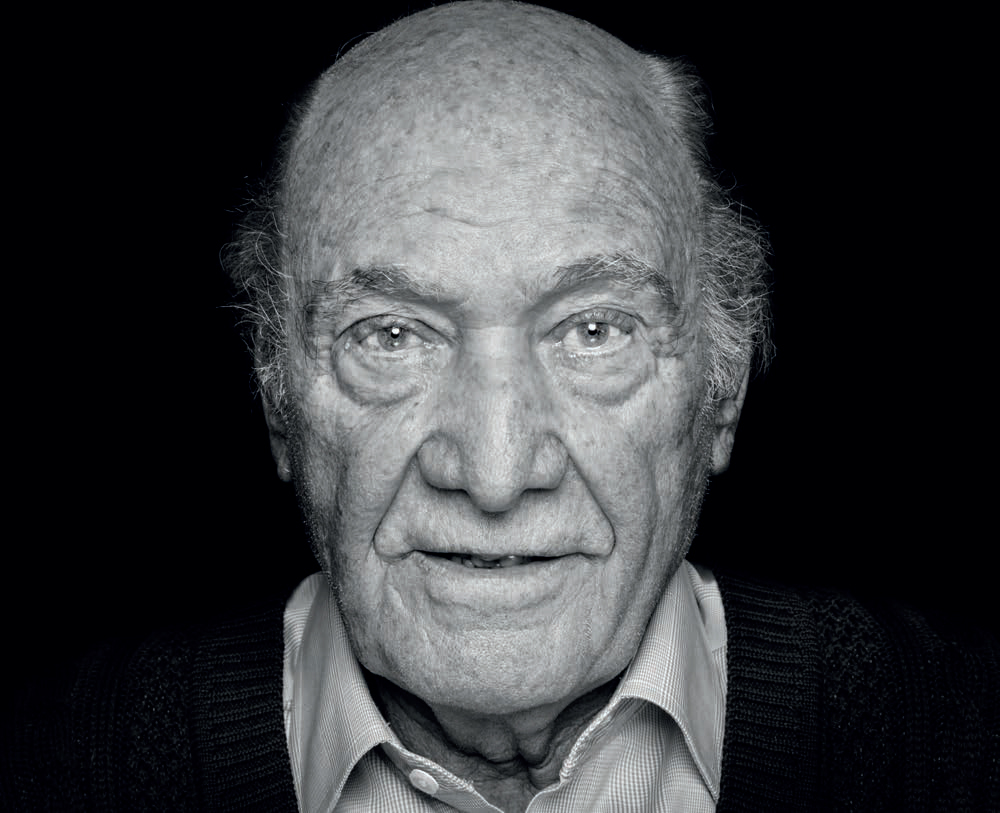

EDUARD KORNFELD

We were deported in a cattle car. We had been traveling for three days when the train stopped. I suddenly heard someone shouting in German: “Get off!” I looked out of the cattle car and saw how the SS were beating people up, so that they would get off the train faster. A woman taking care of her children was walking too slowly; the SS took her baby and threw it on a truck. Old and sick people were also thrown on the truck. They would be immediately gassed.

Born near Bratislava in 1929, Eduard Kornfeld was deported to Auschwitz and other concentration camps; he survived a death march from Kaufbeuren to Dachau. When he was freed from the Dachau concentration camp by American troops on April 29, 1945, he weighed only 60 pounds. His mother Rosa )37 years old(, his father Simon )44 years old(, and his siblings Hilda )11 years old(, Josef )9 years old(, Alexander )7 years old(, and Rachel )4 years old( had been deported and murdered in the gas chambers. Kornfeld arrived in Switzerland in 1949 and spent four years in Davos where he was treated and cured of tuberculosis. He later did an apprenticeship as a jewel setter. He has two sons, a daughter, and seven grandchildren.

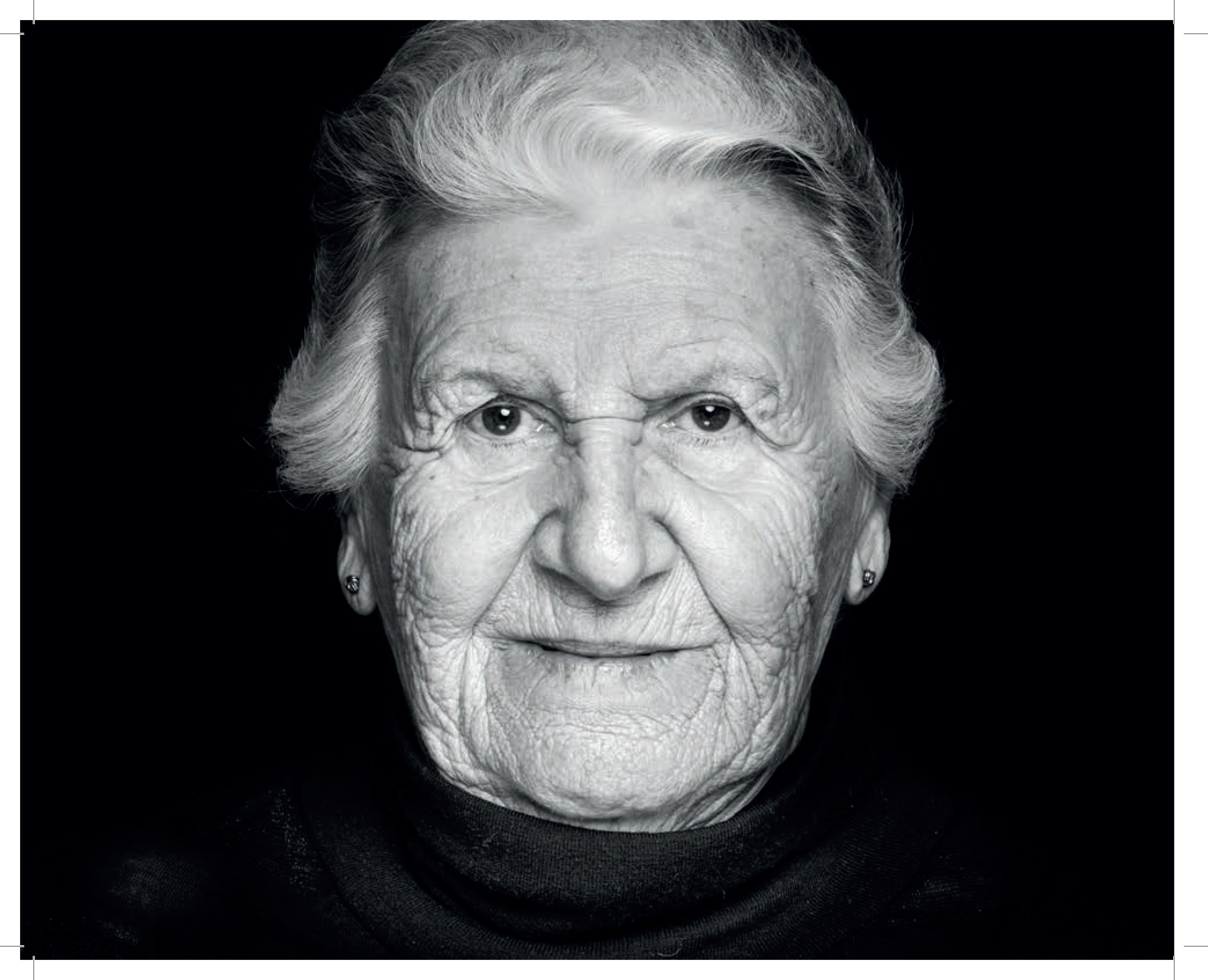

NINA WEIL

Then they tattooed me: 71978. I cried a lot. Not because of pain, no; because of the number. I had lost my name and I was only a number. My mother said to me, “Don’t cry, nothing happened. When we get home, you’ll go to dance school and you’ll get a large bracelet, and nobody will see the number.” I never went to dance school and never got the bracelet.

Nina Weil was born in Klattau (in today’s Czech Republic(, in 1932. She lived in Prague and was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942. Later she arrived with her mother Amalie at Auschwitz. She was twelve years old when her 38-year-old mother died of exhaustion there. Nina Weil survived a “selection” by the camp doctor Josef Mengele and survived a labor camp. After the suppression of the Prague Spring, she and her husband were granted asylum in Switzerland. She worked in a laboratory at the University Hospital in Zurich.

FISHEL RABINOWICZ

At the end of the war, I was in a labor commando in a concentration camp. We had to lay down the steel train tracks. I was the youngest and the shortest in the group. At first, there were 30 of us. At the end of 1944, two people were still alive. How did I make it? I was lucky. I had red, bright red hair. The Germans called me “Rotkopf”, “redhead”. I was given the easiest work.

Fishel Rabinowicz was born in Sosnowiec, Poland, in 1924. In 1943, his 42-year-old mother Sara and his six siblings Esther )16 years old(, Jacob )12(, Frimetta )10(, Benjamin )8(, Mania )6(, and Beracha )3( were killed at Auschwitz. His 18-year-old brother Jeheskiel perished at the Faulbrück concentration camp. His 46-year-old father Israel Josef was shot dead in Flossenbürg. Fishel Rabinowicz, who spent four years in concentration camps and in various forced labor camps, was liberated in Buchenwald. In 1947, he came to Switzerland with a group of survivors in need of recovery. He stayed in Switzerland and became chief decorator of a large department store in the Canton of Ticino. Since his retirement, he has told his life story with graphic images. Fishel Rabinowicz is a widower and has a son.

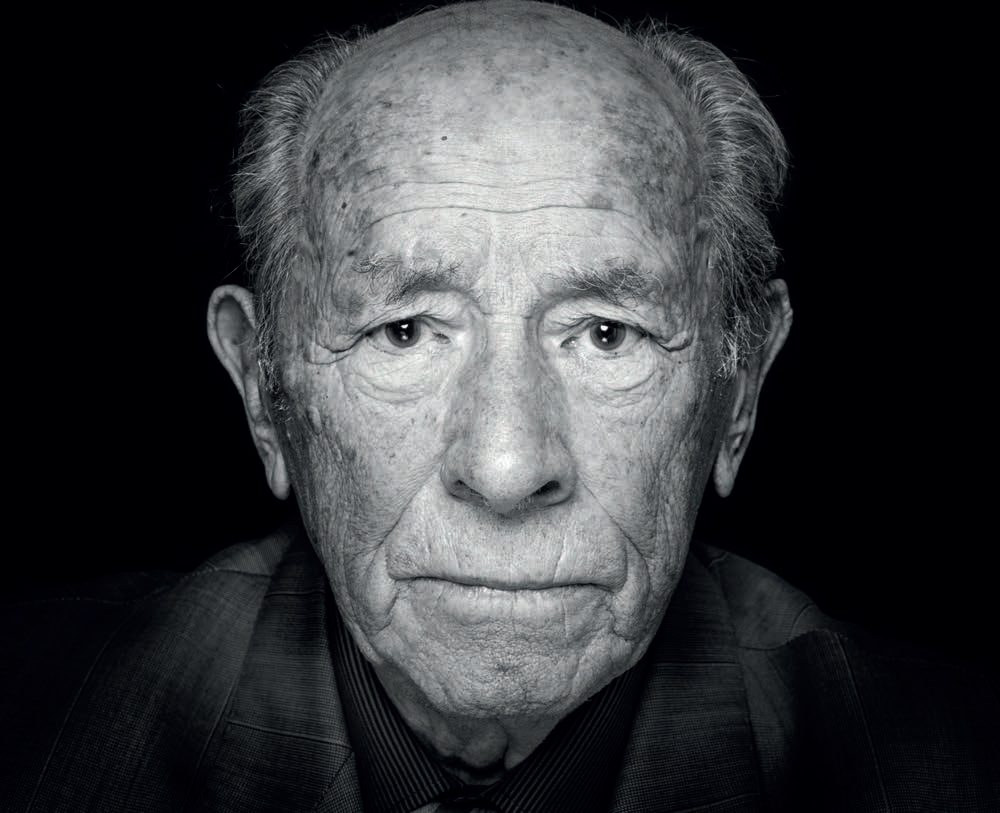

GABOR HIRSCH

At Auschwitz, I worked behind the women’s camp we had to cut grass bricks. I wanted to see my mother once more and I had brought her my bread ration. In fact, we managed to exchange a few words. But I couldn’t give her my bread. She gave me her ration instead. It was the last time I saw my mother.

Born in Békéscsaba, Hungary, in 1929, Gabor Hirsch was deported to Auschwitz at the age of 15. His mother Ella was 48 years old when she was killed in Stutthof. After his liberation, he went to Budapest to earn a high school diploma. In 1956, during the Hungarian uprising, he emigrated to Switzerland via Austria; he studied at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich and became an electrical engineer. Gabor Hirsch is a widower, has two sons and two grandchildren.

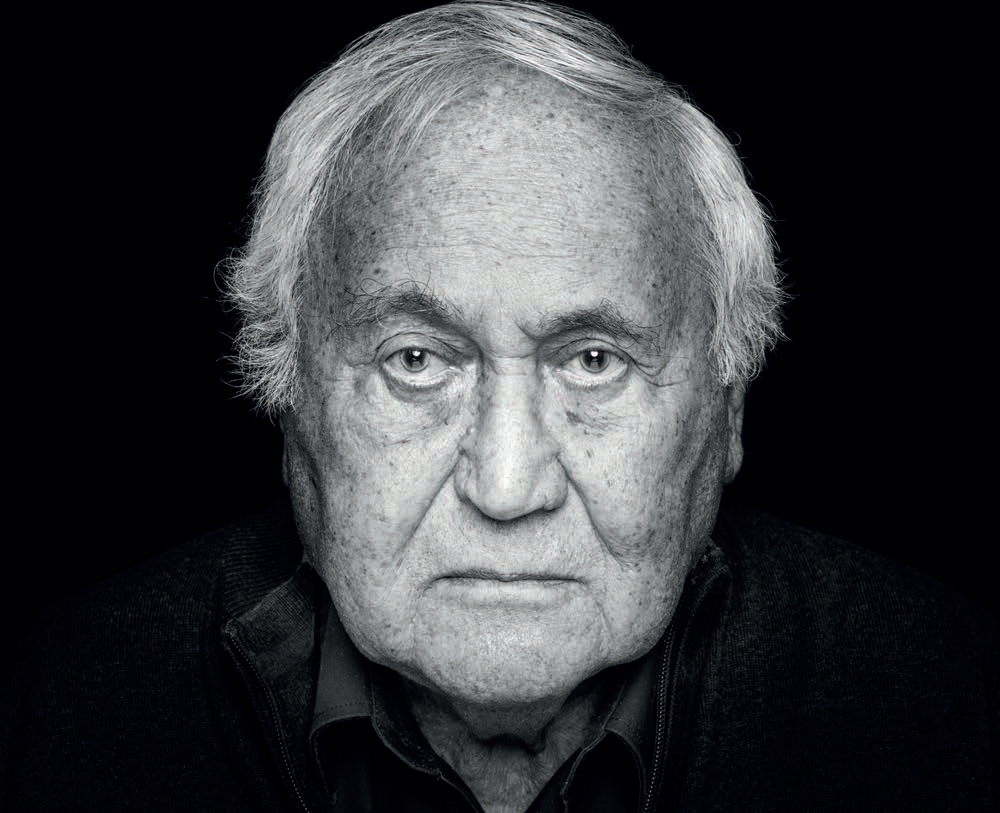

IVAN LEFKOVITS

My mother protected me in Ravensbrück. She would work in additional commandos for an extra ration of soup that she gave me. I learned to read and write; I learned the multiplication tables in the most difficult circumstances. My mother told me, “You will need this in your life”. That was magical. That meant, “you will survive”.

Ivan Lefkovits was born in Prešov )today’s Slovakia(, in 1937. In the fall of 1944, Ivan, his mother Elisabeth, and his brother Paul were deported to Ravensbrück. While he was allowed to stay with his mother, his older brother Paul, who was 15, was separated from them, taken to the men’s camp and later murdered. Ivan survived along with his mother. Ivan Lefkovits came to Basel in 1969 as a professor to establish the new Institute for Immunology. He is married, has a son and two grandchildren.

EVA KORALNIK-ROTTENBERG

The first stop on our escape route was Vienna. At the train station, we were arrested by the Gestapo and brought to spend the night in the notoriously infamous Hotel Metropole, the Gestapo’s headquarters. Harald Feller had organized this to protect our little group. Our mother spent the night in fear and panic. I remember the shiny boots, the German shepherds leashed to the officers, and the gigantic swastika in the marble entrance hall.

Eva Koralnik-Rottenberg was born in Budapest in 1936. Her mother, Berta Passweg, was from St. Gallen, but had lost her Swiss citizenship after marrying a Hungarian national, Willi Rottenberg. Thanks to the efforts of embassy secretary Harald Feller, Eva, her mother, and her sixweek-old sister Vera escaped from Hungary into Switzerland in October 1944. Eva Koralnik headed the international literary agency Liepman in Zurich. She is married, has a son, a daughter, and four grandchildren.

EGON HOLLÄNDER

Then came the British troops. When they freed us, I was almost dead. What I can still remember is the piles of corpses. Nobody can forget this.

“A little white-skinned Slavonic person of about six years old lay very quietly in his cot. He neither moved nor spoke. He had had typhus; he was all skin and bones.“ Excerpt from the book Straight On by Robert Collis, a pediatrician who saved Egon Holländer )born in Martin, today’s Slovakia, in 1938( after his liberation from Bergen-Belsen. Egon Holländer’s mother Elisabeth died there of typhus; she was 34 years old. As the troops of the Warsaw Pact suppressed the 1968 Prague Spring, Egon Holländer, who had a degree in engineering, fled to Zurich. He became a corporate executive in the technology industry. He is married, has two daughters and three grandchildren.

HENRI ELIAS

They told to me, “Be careful, they paid a fake uncle who will take you away. The Jews want to take you with them to Palestine, to fight the Arabs.” I was totally panicked. I was afraid of the Jews; they had crucified the Savior. I needed time to understand that I was myself a Jewish kid.

Henri Elias was born in Borgerhout, near Antwerp, in 1941. His 34-year-old father Leopold, his 35-year-old mother Aurelia-Aranka, and his 7-year-old brother Jacques were deported and murdered, like other family members. Henri was hidden and baptized by force. After liberation, he was declared dead by the Sisters and his godmother, given a fake identity and sent from home to home so as to erase his existence and never return him to his Jewish family. In 1945, his uncle and aunt found clues that he had survived, but could only take him back after a 10-year search and a court decision. In 1971, Elias moved to Switzerland for professional reasons. He got married there and has two daughters.

CHRISTA MARKOVITS

I was always lucky. My cousin, my aunt, my uncle they were all murdered. And we remained alive, but without any merit hidden in a convent, hidden in Budapest. I don’t deserve this. I don’t deserve this luck.

Christa Markovits was born Krisztina Barabás in Budapest in 1936. The whole family converted to Catholicism before the war. Despite their conversion, they were considered Jewish under the racial laws; she and her sister were hidden in the SacréCoeur convent. In 1956, she escaped to Switzerland, where she studied physics and worked for the Paul Scherrer Institute.

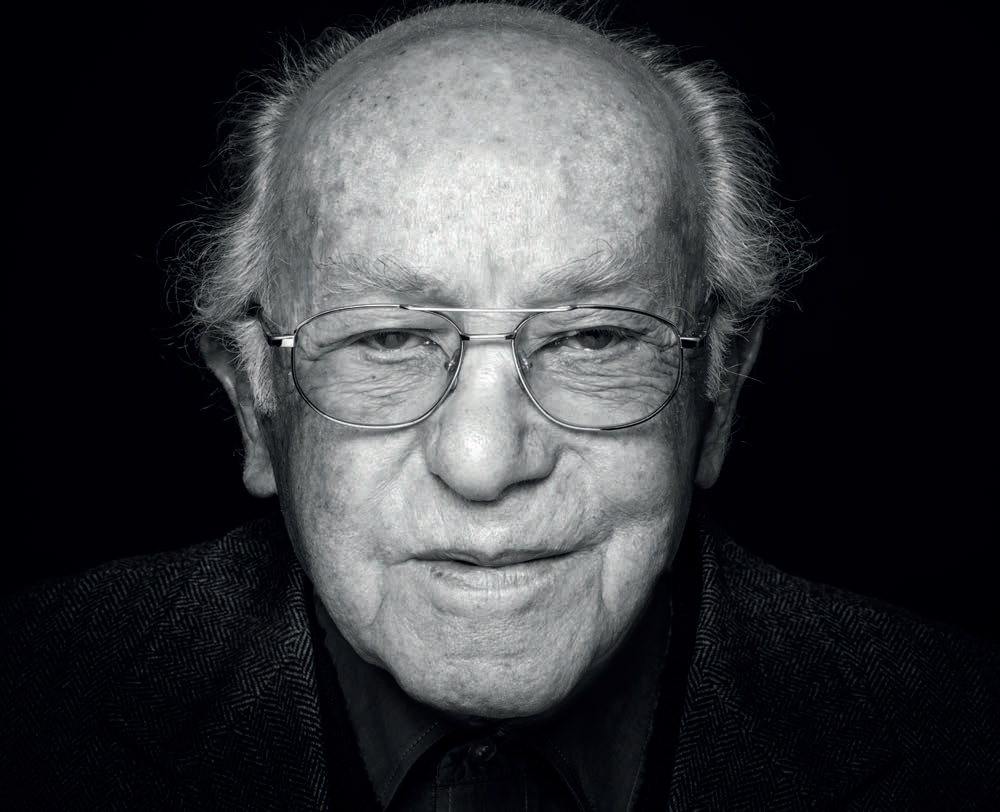

BRONISLAW ERLICH

When I go to bed and turn off the light, I think of my parents and my little brother, who were all murdered. I have sleepless nights. A woman from Berne once thought I should take Valerian drops. I bought myself a bottle. It’s useless.

Born in Warsaw in 1923, Bronislaw Erlich survived under a fake name working as a slave laborer for a German peasant. His 52-year-old father Nachum, his 45-year-old mother Brandl, and his 15-yearold brother Jakob were killed in 1942 either in the Warsaw ghetto or in Treblinka. In 1961, Erlich was recruited by a company in Bern as a professional printer. He later became a successful distributor of printing machines. He is married, has two children, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

KURT SALOMON

When I am asked how I have coped with the Holocaust, I always say the following, “I have no wounds. I have a thick skin.” But it is not right: I was wounded. I do not trust people anymore. I only trust myself.

Kurt Salomon was born in Aix-la-Chapelle, in 1935. His family first escaped to Antwerp and, when the war broke out, to Brussels. In Brussels, he had to wear the yellow star, which he has kept to this day. Kurt Salomon was hidden and reunited with his parents in 1945. They had survived in Mechelen, a transit camp on the way to Auschwitz, by doing painting jobs and working in the infirmary. Kurt Salomon came to Switzerland in 1963, after falling in love with a Swiss woman. He has a son, a daughter )deceased(, and two grandsons.

AGNES HIRSCHI

On his deathbed, my stepfather, Carl Lutz, asked me to make sure that his work would not be forgotten. During World War II, my stepfather was in Budapest, where he saved tens of thousands of persecuted Jews with Swiss letters of safe conduct.

Born in London in 1938, Agnes Hirschi and her mother, who were under threat, lived in Budapest during the war under the protection of the diplomat from Appenzell Carl Lutz, who was deputy consul at the Swiss Embassy. Her mother married Carl Lutz later on. Agnes Hirschi worked as a journalist; she is a widow, has two sons and a granddaughter.

DANIEL GERSON - THE SECOND GENERATION

My father came to Switzerland with the Red Cross in 1945 after the liberation of the Buchenwald camp. He was 19 at the time and completely alone: his father, his mother and his sister had all been gassed in Treblinka. He later married my mother, who was an orphan. My father was fine with that. He couldn’t stand intact families with numerous relatives. It made his own loss much more painful.

Born in 1963, Daniel Gerson is the son of a Holocaust survivor. In the late 1960s, his father became a professor of organic chemistry at the University of Basel. He is a historian who specialiçzes in modern Jewish history and a lecturer at the University of Bern. His coming to terms with his history as a descendant of a Holocaust survivor shows that the experience of the Holocaust has a strong impact on the lives of the second generation.

Concept and text: Pascal Krauthammer and Cristina Schaffner, furrerhugi.ag

Traveling exhibition manager: Gadi Winter

Photography: Beat Mumenthaler

Filmmaker: Eric Bergkraut

Academic advisers: Gregor Spuhler and Sabina Bossert, Archives of Contemporary History, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology,

Zurich Curatorial advice: Bernhard Giger und Pascal Schneiter,

Kornhausforum Bern Digital communication: Manuel Winter and Rafael Winter

English translation: Brigitte Sion